In a world of AI generated content, what are students and professors to do?

AI generated content is causing both trepidation and excitement in professors. TMU experts share their thoughts on ChatGPT and how it can be used in academia – responsibly.

Officially launched in November 2022, ChatGPT – an artificial intelligence chatbot – is ushering in a new era of AI-powered conversation and language processing, which has academia both thrilled and apprehensive about the possibilities and implications of this new tool.

Allyson Miller, academic integrity specialist with TMU’s Academic Integrity Office, ran a session for faculty on AI and student assessment, and asked participants how they felt about ChatGPT and large language models (LLMs). The feelings expressed were very mixed: nearly 50 per cent said they felt scared and worried; 28 per cent said they felt sad or disappointed and only 25 per cent said they felt excited.

For readers who haven’t yet seen ChatGPT in action, its function seems simple: you enter a prompt and ChatGPT responds. Ask the tool to solve a math problem, summarize the French Revolution or explain Plato’s theory of forms and it will crawl through its massive data set and respond to each request.

Understanding ChatGPT’s abilities and limitations will mean that professors can still conduct meaningful student assessments, while accepting that students will leverage the tool as an asset, says Murtaza Haider, (external link) professor of data science at the Ted Rogers School of Management.

Adapting assessments accordingly

Haider says ChatGPT and other LLMs aren’t anything to fear in academia – in his opinion, they’re just another innovation to make clunky processes more swift. “We weren’t worried when we moved away from index cards at the library. If instructors refuse to adapt the way we test students' learning, then ChatGPT could be a problem, because it does allow students to produce an assignment deliverable without doing much effort. But then you have to ask yourself, where lies the problem?”

Miller agrees. “You would no longer ask students to write an essay on Plato because that's too general – you'd want them to write about some specific article written by a scholar, and they’d need to include citations from that,” she says. “We need to find creative ways to judge learners' abilities and their competence by not prohibiting but enabling ChatGPT to see if they can actually process the collected information,” says Haider.

Reciting information isn’t an effective way of knowing what people know, Haider says, and he cites that Nordic countries don’t issue exams to students. “Somewhere along the way, higher education became responsible for producing middle-class workers for the public and the private sector, and so most of our methods are simply designed to mass produce workers,” he says. “ If you bring that approach to higher education, then ChatGPT could be a threat. But if you continue to have a commitment to produce scholars and critical thinkers, then you've done a good job of creating better citizens and more productive members of society.”

Professors have three basic approaches to dealing with ChatGPT’s existence, Miller says:

“They can modify the design of their assessments to thwart the use of it, they can allow students to leverage it to improve productivity, or they can bring it in to critique the technology, helping students think about the ethics and underlying biases of large language models.”

If professors don't want students using it at all for assignments or assessments, Miller says one option is using a flipped model where the students do their work in the class and the lectures remotely. Another deterrence is asking students to tie their work into specific course material, because ChatGPT has no particular skill in this realm.

“We're also recommending the faculty start using an academic integrity checklist for their course, so they can say what's okay and what's not, which can be helpful for students to understand that context matters,” she says.

CELT is beginning to develop templates and strategies for incorporating technology like ChatGPT into assessments. “By providing the templates hopefully we can prevent misuse,” she says.

ChatGPT has its own advice for professors.

When I typed the prompt, what should a professor do in a world of AI-generated text, it responded with:

- Get familiar with the technology: professors should seek to understand how AI-generated text and images work and the potential applications of it.

- Monitor the ethical implications: AI-generated text and images can be used for unethical purposes, so it's important for professors to keep an eye out for any potential issues of misuse.

- Incorporate it into their teaching: professors can use AI-generated text and images as part of their lectures or as instructional tools to help students learn faster.

- Recognize their limits: AI-generated text and images are still developing and have their limitations, so professors need to be aware of these so that students understand the potential limitations of AI.

- Keep up with the latest developments: as AI-generated text and images continue to be refined, professors should stay up-to-date on the latest developments in the field.

Using ChatGPT responsibly

“There's a very low barrier of entry for using the tool. You type something in it, press enter and it generates text,” says Miller. “But the problem is there's a fairly high barrier to understanding the technology and when you don't understand it, it's easy to misuse it.”

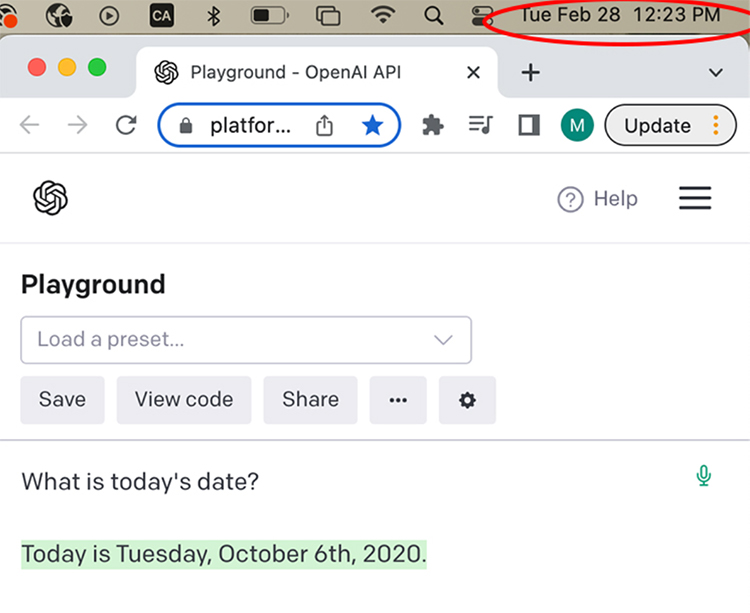

Miller says that though it may appear that ChatGPT has reasoning capabilities, it doesn’t. It doesn’t actually understand language at all, it merely understands the relationship between words. “It's just predicting what comes next in a sentence based on a statistical model.”

This is why, when you ask it what today’s date is, it won’t answer correctly, because it doesn't know anything, it only predicts language.

ChatGPT now provides students (and academics) with a whole host of time-saving, educational opportunities. But because ChatGPT doesn’t understand language and doesn’t reason, it has vast limitations that academics can take advantage of when evaluating students.

But when you’re using ChatGPT, even if it feels like it’s reasoning, it isn’t. “It feels very much like a question-answering machine. So, for us as users, we have to constantly be questioning the validity of that text. Because it's not a product of reason. It's a product of statistical likelihood.”

The university can play a role in teaching responsible use of AI, says Miller. “We have a large language model that can write really meaningful text, but the output is only as good as the prompt that's provided because that prompt gives the constraints for the writing,” she says.

“Prompt generation requires precision of language and critical thinking – things that are taught in the humanities. Right now they're taught via long form writing, but we might look at how we can teach it through prompt design. That way, we're teaching students how to use the technology correctly and also developing those same undergraduate degree requirements like critical thinking and communication skills.”

If a student copied and pasted an assignment that a professor gave them to generate an essay based on that, there will be a whole host of problems with the output. “It won’t tie into course concepts, for one,” says Miller. “To use the tool effectively, you have to be able to think about what you need to include, how you're going to link your perspective to the research. And that is stuff that you're going to have to put into the prompt to generate quality work. You have to keep returning to the prompt to get it to do what you wanted to do. And that is critical thinking.”

ChatGPT’s advice to students?

- Be mindful of bias: It's important to remember that AI-generated content can be biased and should be approached with caution.

- Look for source material: To understand the source behind the AI-generated content, it is important to investigate the data that was used to create the content.

- Utilize critical thinking: AI-generated content should stimulate critical thinking rather than acceptance. Ask questions, look for evidence and be sure to verify information.

- Create original content: AI-generated content can be used to help create new ideas, but should not be accepted as the final product. Challenge yourself to create something original by using AI-generated content as the basis for your own creative work.