Addressing systemic anti-Black racism in Canada: progress, challenges and pathways forward

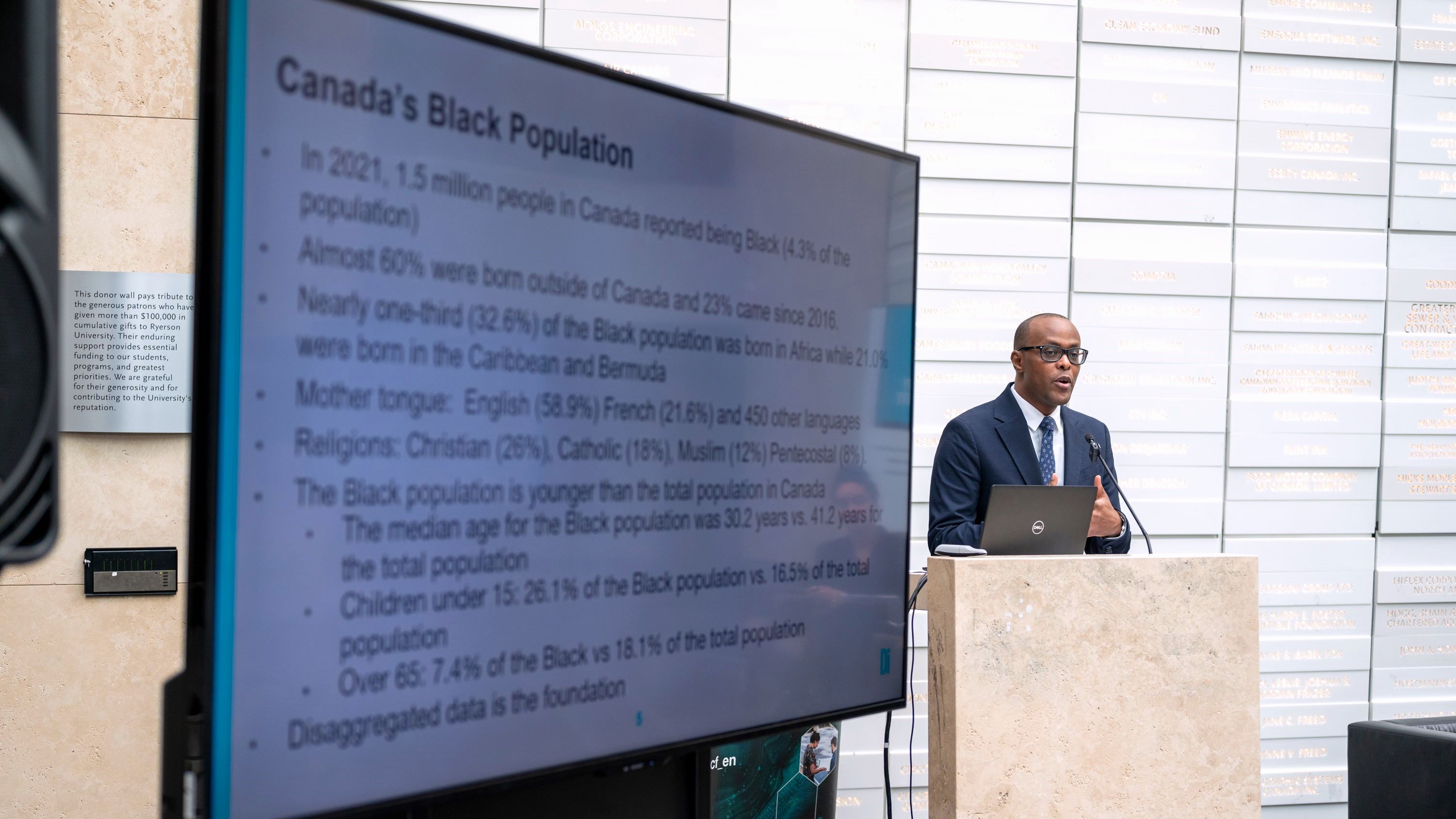

Mohamed Elmi, executive director of the Diversity Institute, and researcher on ADaPT for Black Youth and Study Buddy. (Photo credit: Clive Sewell)

The murder of George Floyd focused attention worldwide on the realities of anti-Black racism. In response, we saw a rise in commitments by governments, corporations and communities to addressing systemic anti-Black racism. New organizations such as the BlackNorth Initiative, the Black Opportunity Fund, Federation of African Canadian Economics (FACE), along with legacy organizations such as the Black Business and Professional Association (BBPA), Caribbean African Canadian Social Services and others, have worked across sectors to advance the economic and social development of the Black community. And more enhanced disaggregated data about the Black population in Canada have become available to allow us to understand where we are and where we need to go.

We know that education lays the foundation: it is generally the strongest predictor of social mobility in Canada, enabling people to leapfrog their parent’s socio-economic status. Generally, poverty rates among racialized groups decrease from one generation to the next. But this is not true with the Black population.

Among the third generation or more, the poverty rate (12.1 per cent) is more than double that of the non-racialized population (6 per cent). There are no simple solutions to complex problems, and there are still limits to disaggregated data, but anti-Black racism in education, employment and leadership are all factors.

The education system has not served the Black community well, with numerous studies laying bare the realities of anti-Black racism, exclusion, streaming and “over-policing,” even in the classroom. We also know that Black youth are more likely to drop out and are less likely to attend university. The 2023 study, “Tackling Anti-Black Racism in Education” by the Ontario Human Rights Commission (OHRC), “acknowledges a crisis of systemic anti-Black racism in Ontario’s publicly funded education system, exacerbated by the recent significant rise in societal hate, particularly directed towards Black individuals, and immediate action and solutions are imperative.”

Nevertheless, education gaps between the Black community and others are narrowing, driven largely by the infusion of highly educated newcomers. The most recent Statistics Canada data highlights the growing diversity of the Black community, which accounts for 4.3 per cent of the Canadian population.

Currently, more than 60 per cent are immigrants, mostly from Africa (55.3 per cent) and the Caribbean (35 per cent). In 2021, about one-third of the Black population aged 25 to 64 held a bachelor’s degree or higher, which is nearly the same as the whole population.

This should be transformative, but despite narrowing the education gap, Black people are under-employed and underpaid. Statistics Canada data shows that 16 per cent of Black workers with a bachelor’s degree or higher from a Canadian institution worked in occupations that require a high school diploma or less, compared to 11.2 per cent of others. Black Canadians earn 75.6 cents for every dollar a non-racialized worker earns.

In-depth analysis of data, for employers, including the Government of Canada, shows ways in which anti-Black racism becomes embedded in employment systems.

It was particularly hard to see the Canadian Human Rights Commission, of all institutions, found to have systemic anti-Black racism. Employers must examine how they construct jobs, recruit, retain and promote their employees, and build inclusive cultures and accountability frameworks. They must match their good intentions with concrete actions, and there are tools available to help them do it.

We know that education lays the foundation: it is generally the strongest predictor of social mobility in Canada, enabling people to leapfrog their parent’s socio-economic status. Generally, poverty rates among racialized groups decrease from one generation to the next. But this is not true with the Black population.

Representative leadership signals who belongs and shapes aspirations and engagement. It also affects intergenerational wealth. For 15 years, the Diversity Institute’s DiversityLeads has tracked under-representation. It was the first to track Black people serving on boards and in senior leadership roles. Its latest report with the Future Skills Centre and the 30+% Club examines 783 TSX companies, including 235 S&P/TSX Composite Index firms to examine the impact of voluntary codes such as the BlackNorth Initiative (BNI) and 30%+ Club.

Among BNI signatories, 3.34 per cent of TSX board members were Black compared to 1.6 per cent representation among non-members. Similarly, BNI companies in the TSX have a higher representation of Black people on their executive team compared to non-BNI companies (2.8 per cent vs 1.5 per cent). There is still much to be done: it is one thing to advance to a leadership role and another thing to stay there. It is crushing to see Black trailblazers, particularly women, held to higher standards without supports, and pushed over glass cliffs.

The work must continue. “What gets measured gets done” and data is the foundation. Recently, the Employment Equity Act Review Task Force recommended adding the Black community and the 2SLGBTQI+ community as distinct designated groups under the Employment Equity Act. This is an important step to recognize the distinct problem of anti-Black racism and to put in place measures to track and report on progress. The United Nations declared 2015 to 2024 the International Decade for People of African Descent, but we have a long way to go. Canada is pushing for an extension to the proclaimed decade to ensure we see concrete action and progress, not just here, but globally.

This content was produced by Randall Anthony Communications as part of the Black History Month special feature, published in the February 23, 2023 The Globe and Mail. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.